Peter Werbe bikes, plays handball, does tai chi and still works for social justice with the same fervor that he had in the 1960s.

Last weekend, the longtime political activist participated in a Detroit demonstration to stop hate aimed at Asian Americans. This weekend, he’ll probably be fighting the good fight somehow, somewhere, and he’ll be doing it with a spirit of protest that stays, to lift a Bob Dylan lyric, forever young.

Yet, at 80, Werbe isn’t sure what is perceived as radical anymore.

”These days, I’m not even sure what it means to be a revolutionary. Sometimes, it might mean you want Medicare for all,” he says. According to Werbe, the right wing of American politics so controls the discourse that “someone who wants reforms along the lines that most conservatives in Europe support, like a national health system, are said to be these radical leftists.”

Radicalism in all of its retro glory is captured in Werbe’s new novel, “Summer on Fire,” which is set mostly in 1967 Detroit.

“Summer on Fire,” published by Black & Red Books, is described as a fictionalized memoir in which the characters spend seven weeks living in the counterculture landscape that encompasses the Detroit rebellion’s five days of civil unrest, a large anti-Vietnam War march, the Grande Ballroom’s regular performances by soon-to-be rock legends, drugs, sex, anarchism, the Black Panther Party, the White Panther Party and even a subplot involving a potential bombing.

Like two current Oscar-nominated movies, “The Trial of the Chicago 7” and “Judas and the Black Messiah,” the book plunges you back into an era of rebellion that did, to a certain extent, change the world.

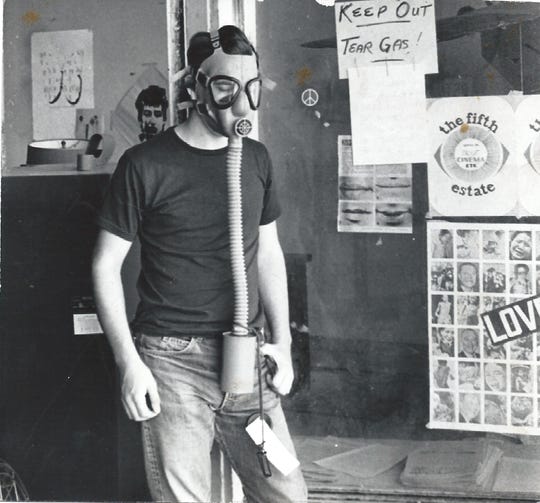

Fifth Estate co-editor Peter Werbe exiting newspaper office with gas mask, July 24, 1967. A National Guard tear gas grenade was shot through the window during the overnight curfew. (Photo: Fifth Estate Papers, Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan)

But at its heart, Werbe’s novel is a time-travel trip that evokes what it was like to be part of the Fifth Estate underground newspaper, the iconic Detroit publication launched in 1965 that had an impact far beyond its counterculture reach.

In the Detroit region, Werbe is probably best known for his radio career. A former deejay for WCSX-FM, WWW-FM and WABX-FM, he was an airwaves staple to generations of listeners on “Nightcall,” the WRIF-FM phone-in talk show that lasted from 1970 to 2016. Werbe was its host for most of what’s touted as the show’s record-setting run.

Yet Werbe’s front seat to the tumultuous ’60s was the Fifth Estate, which lives on as a magazine and which he still serves as an editorial board member.

More: Novel by Elmore Leonard about Detroit homicide cop to be adapted for FX series

More: Local Iraqi American film, novel aims to bring unity to Chaldean, Muslim communities

The Fifth Estate, which was among the first underground newspapers of the 1960s, is the home base for most of the novel’s main characters. They include Paul and Michelle, who are somewhat inspired by Werbe and his wife, Marilyn, but not totally, of course. As Werbe stresses, this is fiction, not autobiography.

He seems amused by questions regarding how closely his character hew to real life. “A neighbor of mine who edited a chapter and made some very important suggestions in the drafts, she said, ‘I didn’t know Marilyn could ride a motorcycle.’ And I said: ‘She can’t. She didn’t. I made it up.’”

“Summer on Fire,” a novel by Peter Werbe, centers on a group of young political activists across many turbulent weeks in 1967 Detroit. (Photo: “Summer on Fire”)

So why did he choose the novel form instead of autobiography? “The frank answer to why I didn’t do a memoir is I don’t’ have enough material or memory to do it,” says Werbe, who admits he is amazed by friends who’ve kept careful, detailed journals of their experiences.

“I never had any sense of preserving history. … We thought we were simultaneously going to experience world revolution and the age of Aquarius. We didn’t think historians would be poking around wondering who said what when.”

Herrada says there’s still enough material in the paper’s archives to attract scholars, writers and filmmakers from around to world who are researching various subjects, “not the least of which is what was happening in Detroit in the 1960s and ’70s.”

The Fifth Estate was “the counterculture’s source for music, politics, and the arts in general,” according to Herrada. “It wasn’t just a political paper or just a hippie paper, but spoke to all the communities that defined the 1960s in politics, culture, and the arts.”

The Fifth Estate also was an early part of the Underground Press Syndicate, a national network that served as a sort of Associated Press for nearly 500 alternative papers at its height.

While the Fifth Estate was a forerunner to today’s Metro Times in Detroit, it also had much influence on the city’s mainstream newspapers, which “realized they were being left behind by the younger generation of readers by ignoring people of color and the youth,” says Herrada.

She points out that, in the wake of the Fifth Estate, the Free Press started paying more attention to rock music and other content aimed at hipper readers.

Peter and Harvey Ovshinsky at the Detroit Historical Museum on Sept. 26, 2015, at a symposium noting the 50th anniversary of the Fifth Estate. (Photo: Rebecca Cook)

Harvey Ovshinsky, who founded the Fifth Estate in 1965 at age 17, puts it another way. “We were the original media disruptors. The internet, the web, social media, they’re latecomers to the party,” he says.

Ovshinsky is the inspiration for the character of Sidney in “Summer on Fire.” He says he was flattered to be included in Werbe’s novel and recognized himself in some of Sidney’s qualities, but not in others.

“I was grateful that he thought enough of our relationship (to have a character based on me),” says Ovshinsky. “Our collaboration was very important to both of us. He’ll be the first to say that. I’ll be the second.”

In the “Scratching the Surface” chapter on the Fifth Estate, Ovshinsky credits Werbe’s role in turning the newspaper “into something more forceful and persuasive and, eventually, more vociferous and radical than I ever could have imagined. Or even, at times, preferred.”

Describing their working relationship and long-lasting friendship, Ovshinsky writes that, as he has told Werbe, “We were like the Beatles, only I was Paul and you were John.”

Sign on headquarters of the Detroit Committee to End the War in Vietnam, 1101. W Warren, announcing the April 26, 1968 Student Mobilization world-wide student strike. Windows had been broken previously by right wing vandals. Fifth Estate office is next to it on the right with its windows boarded, also the victim of vandalism from the right. (Photo: Fifth Estate Papers, Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan.)

“Summer on Fire” is entwined with Detroit history. In that sense, it has something in common with the 2020 novel “Black Bottom Saints” by Alice Randall, which is filled with vivid sketches of real African American celebrities, artists, doctors, lawyers and sports stars of Detroit’s bygone days. If your curiosity is piqued by Werbe’s novel, you might leave it wanting to read 10 more books on Detroit’s counterculture movements.

More: New museum exhibit on Detroit’s painful summer of 1967 is illuminating, immersive

More: New novel celebrates now-gone Detroit neighborhood Black Bottom

There are scenes in “Summer on Fire” that seem meant for a movie — and stretches of dialogue that are as politically charged and confidently righteous as an Aaron Sorkin monologue.

In one scene, Detroit’s iconic rock band the MC5 rehearses at full volume in the basement of the Fifth Estate’s office as staffers design the layout of the latest issue. In another, poet and activist John Sinclair does a dramatic reading of his latest fiery editorial.

Peter Werbe in photo taken February 15, 2021, in the WRIF-FM studios as part of the RIF’s 50th anniversary. (Photo: Peter Werbe)

Werbe says one of the most realistic parts of the book involves Paul and Sidney teaming up to report on the chaos and violence that erupted after Detroit cops raided a party at a blind pig on 12th Street. The rebellion against systemic racism and police brutality resulted in the National Guard and federal troops being deployed to the city and 43 deaths.

“Harvey Ovshinsky and I, the Sidney character, really were out there and going to this A&P store on Trumbull, and going to Grand River and West Grand Boulevard, and seeing the street being looted, and being threated by a National Guardsman, and having the National Guard throw a tear gas grenade through our windows. That all happened.”

The hardest portion for him to write was about the horrific events at the Algiers Motel, where three African American teenagers — Carl Cooper, 17, Aubrey Pollard, 19, and Fred Temple, 18 — were killed. Several other people were beaten and terrorized. Three white Detroit police officers were charged in the events related to the deaths. None of them was convicted.

Werbe says writing about that night affected him deeply. He has never seen the 2017 film “Detroit” that depicts what happened in brutal detail. “I can’t watch movies like that,” he says. “I get actually palpably angry and saddened.”

Werbe takes a road less traveled in the pacing and style of his novel. He pauses the narrative at certain moments to delve into Detroit history, even if it means leaving the characters behind to spend several paragraphs or pages on topics like hate groups in Michigan or the 1925 Ossian Sweet trial.

Werbe recalls how a novelist friend told him “Summer on Fire” reads like a Fifth Estate article. “And I said, ‘Well, thank you!,'” Instead of taking her advice to focus more on character development and other literary techniques, Werbe chose to stick to his path. “I want (the book) to tell the story of people interacting with these historic events,” he says.

Werbe says he’s been surprised and gratified by the positive response to his novel, which has been doing well at metro Detroit stores like the Book Beat in Oak Park and Source Booksellers in Detroit. Its popularity may stem partly from its echo of what’s happening today in the fight to save democracy and end social injustice.

So is Werbe pessimistic or optimistic about the current outlook for America?

”It depends on what day you wake me up,” he says. “The fundamental problems haven’t been solved, and whether or not this new administration, which is going further than anybody expected towards the direction of what you would call social democracy politics in Europe, intends to deal with the worst abuses … whether it’s going to be enough (in) time, I don’t know.”

What does encourage Werbe is the widespread support for the Black Lives Matter movement that was sparked by the death of George Floyd in May 2020. Millions upon millions of people turned out for global marches against systemic racism, something even a longtime activist like him hadn’t seen before.

Wherever people gather to address the wrongs of society, the spirit of the 1960s lives on. Watching the outrage of contemporary young people pop up in unexpected places is enough to impress even a well-known Detroit anarchist like Werbe.

“Two hundred people walking down the streets of Pleasant Ridge yelling, ‘Black lives matter!’ I was never so flabbergasted (by) anything in my life,” he says.

Contact Detroit Free Press pop culture critic Julie Hinds at jhinds@freepress.com.

Read or Share this story: https://www.freep.com/story/entertainment/arts/2021/03/28/summer-on-fire-novel-peter-werbe-1967-detroit/6981688002/

Credit: Source link